Articles

Content That Matters

From Giffard to the Future: Are Airships the Forgotten Answer to the Challenges of Modern Aviation?

Author/Editor Maria Anna Furman

A 19th-Century Dispute That May Change the 21st.

There is no haste in archives. Paper yellows slowly, ink fades discreetly, and the names that once electrified public opinion wait patiently to be read again. The history of airships, before it became a romantic memory of the Zeppelin era, was the subject of fierce scientific debate. It was not merely a technical experiment; it was a dispute over priority, over the direction of progress, and over the memory of invention.

The path to these documents was not simple. Reaching the original descriptions, the Academy of Sciences reports, the polemical articles, and the emotionally charged opinions of scholars required patience and careful searching of digital libraries and archives, which rarely lead the reader directly to the goal. Many materials were scattered, briefly described, and sometimes incorrectly catalogued. And yet, the deeper I entered this field, the more clearly it became evident not the story of a single invention, but that of an entire era struggling to conquer the air.

Gaston Tissandier’s 1872 book, devoted to Henri Giffard’s experiments of 1852 and 1855 and to Dupuy de Lôme’s 1872 project, is not merely a technical account. It is a polemical document. The author does not conceal his sympathy for Giffard and consistently argues that it was he, not the later constructor financed by the state, who laid the foundations of aerial navigation.

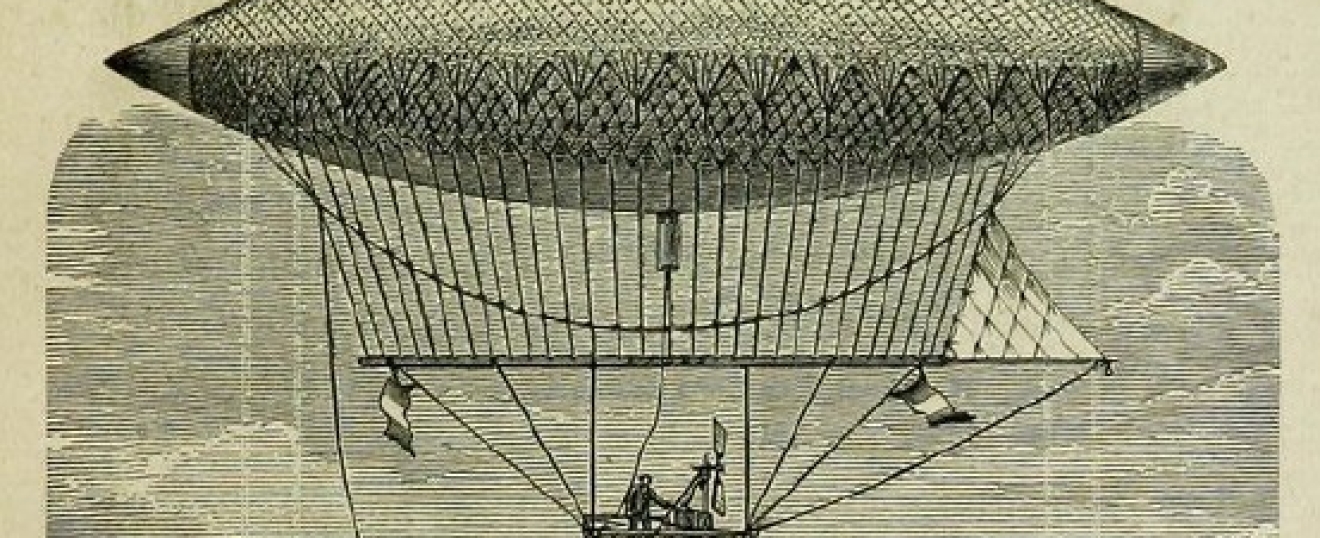

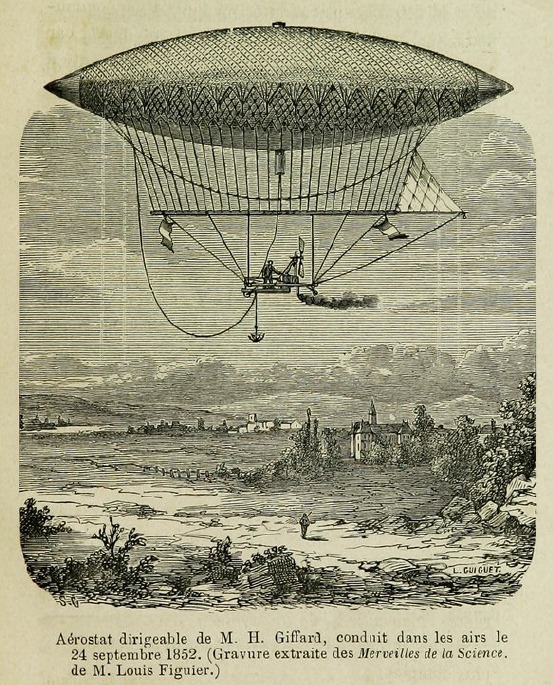

In 1852, Henri Giffard accomplished something that in the mid-19th century seemed almost contrary to the logic of nature: he rose into the air in an elongated balloon powered by a steam engine. The aerostat measured approximately 44 meters in length, contained nearly 2,500 cubic meters of hydrogen, and was equipped with a propeller driven by a three-horsepower engine. This was not merely a demonstration of floating; it was an attempt to give the balloon its own velocity relative to the air. Giffard proved that it was possible to control the direction of flight under favourable atmospheric conditions.

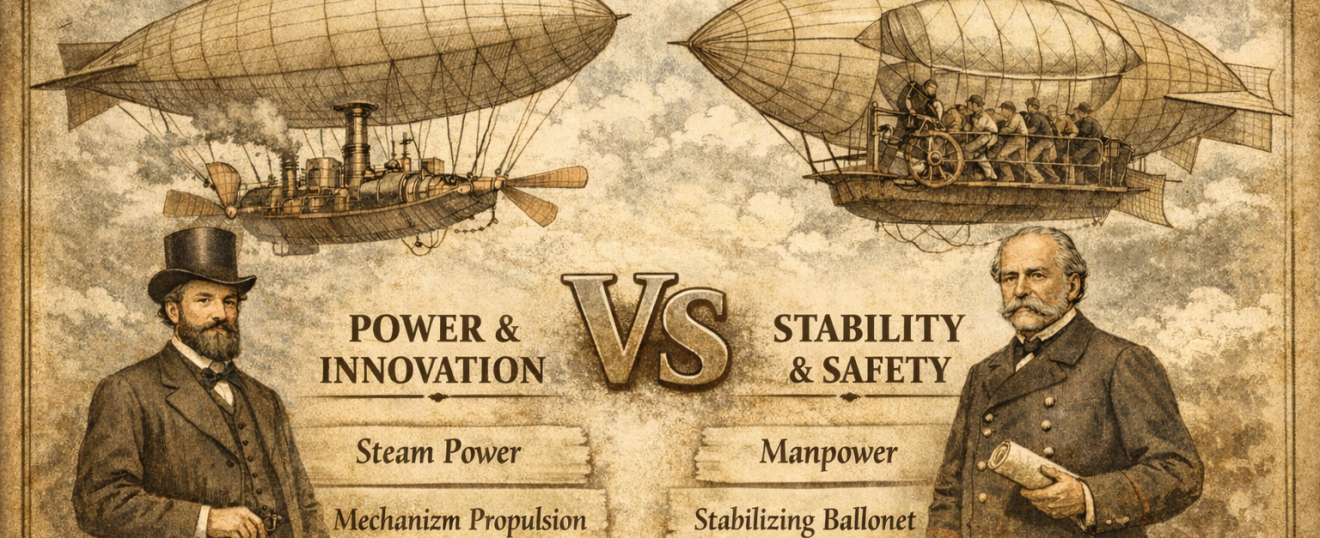

Twenty years later, in an entirely different political context during the Siege of Paris, the subject returned. The Government of National Defence allocated funds for the construction of a steerable balloon capable of maintaining communication and potentially serving military purposes. The project was entrusted to Dupuy de Lôme, a renowned designer of ironclad warships. In 1872, a new aerostat was built, larger in volume, 36 meters long and nearly 15 meters in diameter, equipped with a large propeller driven by eight men turning a crank.

The February 2, 1872, flight was considered a success. The balloon remained stable, responded to the rudder, and achieved a speed of approximately 2.8 meters per second relative to the air. Yet for Tissandier and part of the scientific community, this was not a breakthrough but a return to the starting point. Rather than strengthening the case for mechanical propulsion, the steam engine was abandoned in favour of human muscle power. In the eyes of the book’s author, this was a step backwards, a renunciation of industrial energy in favour of a solution that was safer, but less ambitious.

The dispute did not concern technical parameters alone. It concerned the very understanding of progress. Was improving structural stability through the use of an internal air ballonet to maintain the envelope’s shape sufficient innovation to speak of a new era? Or did the true problem of aeronautics remain, as before, the question of engine power and thus the ability to overcome the wind?

In light of today’s knowledge, it is clear that both constructors operated within the technological limits of their era. Engines were heavy, materials were limited, and hydrogen was dangerous. Yet Giffard was the first to combine an elongated aerostat with mechanical propulsion, thereby anticipating developments. Dupuy de Lôme demonstrated structural stability but did not increase power. And without power, there was still no true domination over the wind.

Here emerges a question that recurs in the context of the 19th century: can airships regain their place?

Today, in an era of the climate crisis and the search for alternative modes of transport with a low-carbon footprint, the concept of large, slow, yet energy-efficient airships is once again being examined by engineers. Contemporary projects employ lightweight composites, modern propulsion systems, precise meteorology, and advanced aerodynamic modelling. What in 1852 was an experiment of almost heroic audacity can today be calculated by a computer before the first flight.

The history of Giffard and Dupuy de Lôme reveals something more: technology does not develop linearly. Sometimes vision outpaces material capabilities. Sometimes a solution appears too early. Sometimes it is forgotten, only to return decades later in an entirely new context.

Perhaps that is why returning to these 19th-century sources has significance beyond the purely historical. This is not merely a dispute between two constructors. It is a story about the memory of innovation. About how easily credit can be attributed to the one who acts at a politically favourable moment. And about how progress can be quiet before it becomes obvious.

Airships did not disappear because they were impossible. They disappeared because aeroplanes emerged faster, more dynamic, better suited to the logic of the 20th century. But the 21st century is governed by different questions. And among them is this one: can slow, majestic flight once again become an answer to contemporary challenges?

Perhaps the future of aviation will, paradoxically, look once more toward the 19th century.

Author/Editor Maria Anna Furman

Source: Gaston Tissandier (1843–1899), Les ballons dirigeables : expériences de M. Henri Giffard en 1852 et en 1855 et de M. Dupuy de Lôme en 1872, Paris: Édouard Blot et Fils Aîné, 1872.