Articles

Content That Matters

Author/Editor Maria Anna Furman

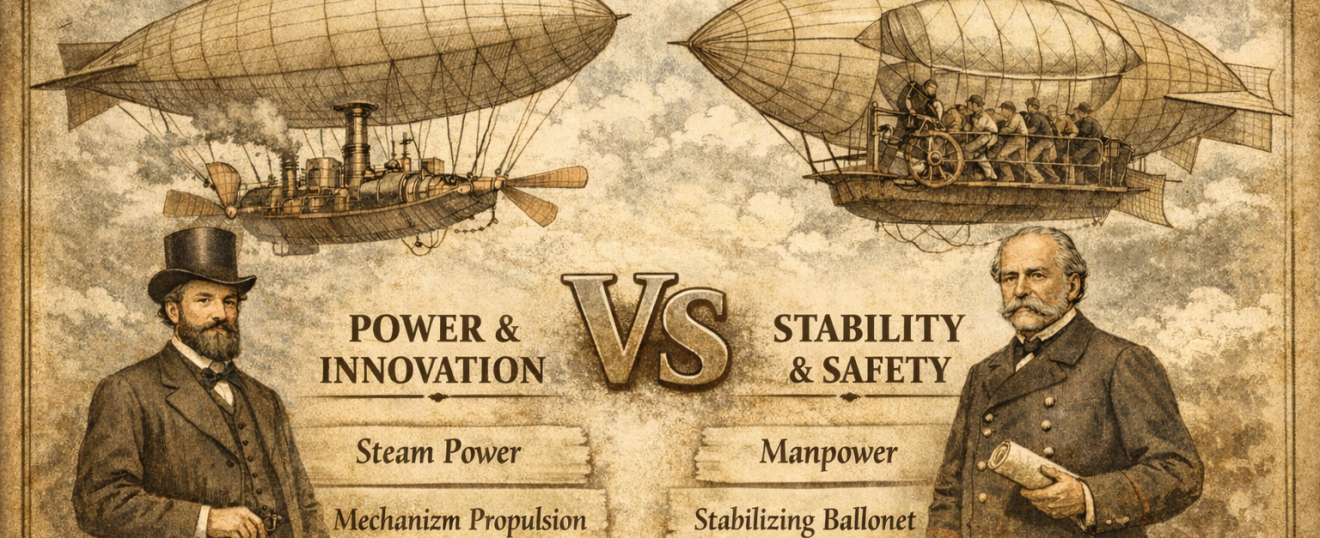

An Analysis of a Technological and Symbolic Conflict of the 19th Century

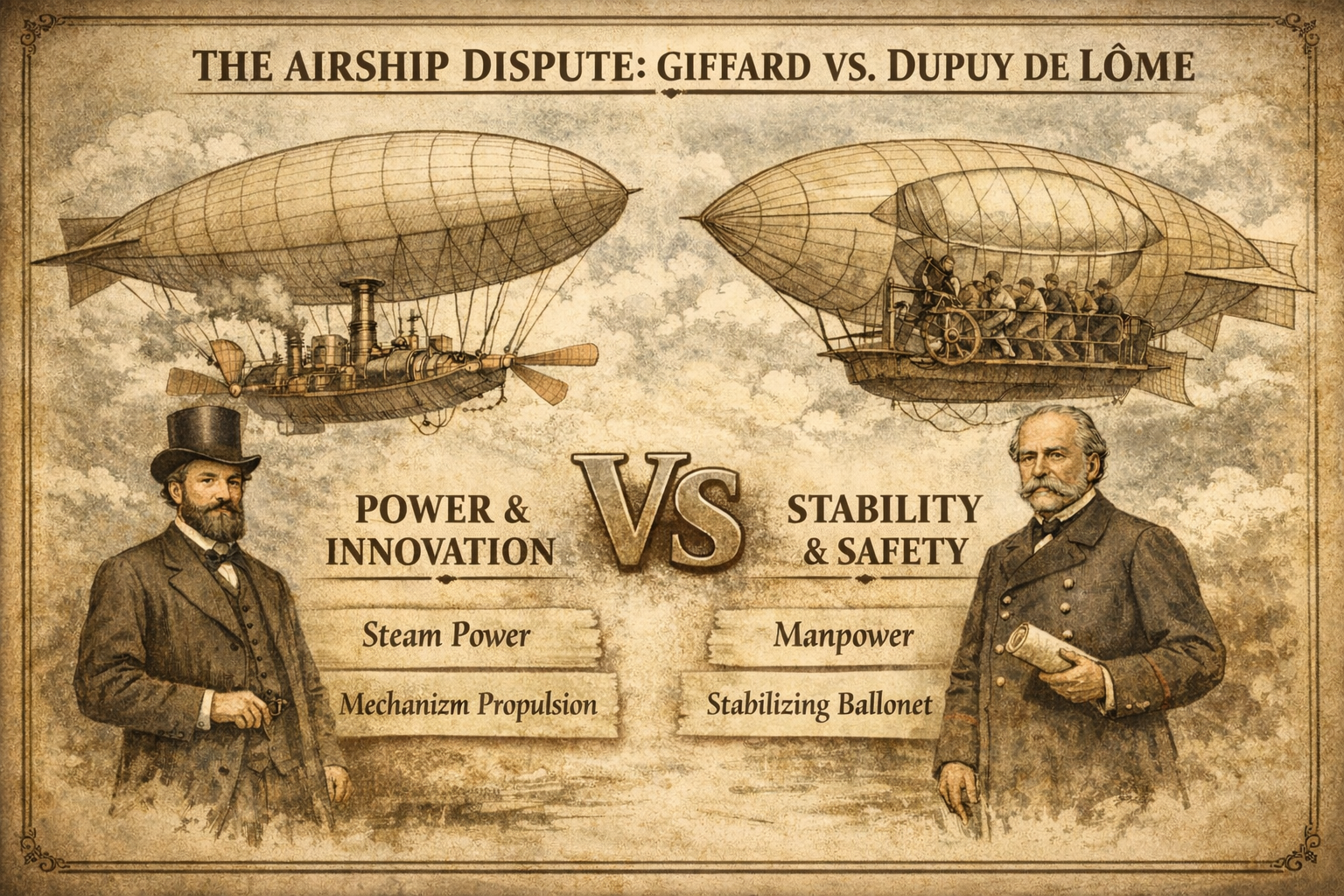

The conflict between Henri Giffard and Dupuy de Lôme was not merely a structural difference nor a rivalry between two engineers. It was a dispute over the definition of progress, over the pace of modernisation, and over who, and under what circumstances, secures a place in the history of technology. In light of contemporary documents, especially Gaston Tissandier’s 1872 work, it becomes clear that the discussion concerned far more than flight parameters.

1. Chronology and Priority

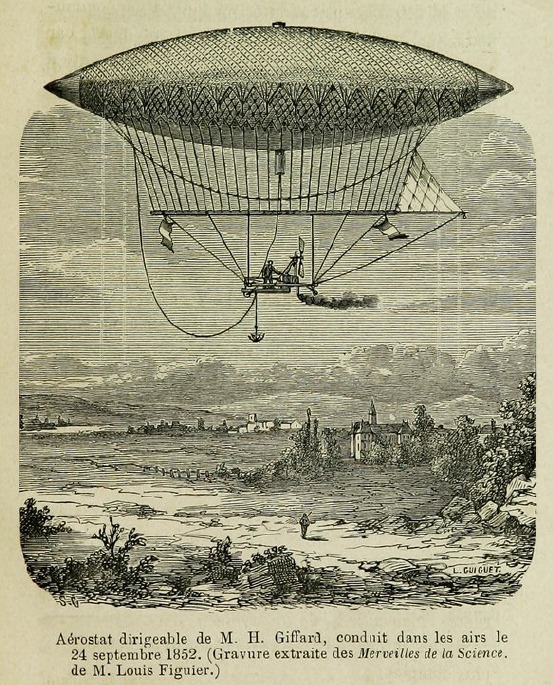

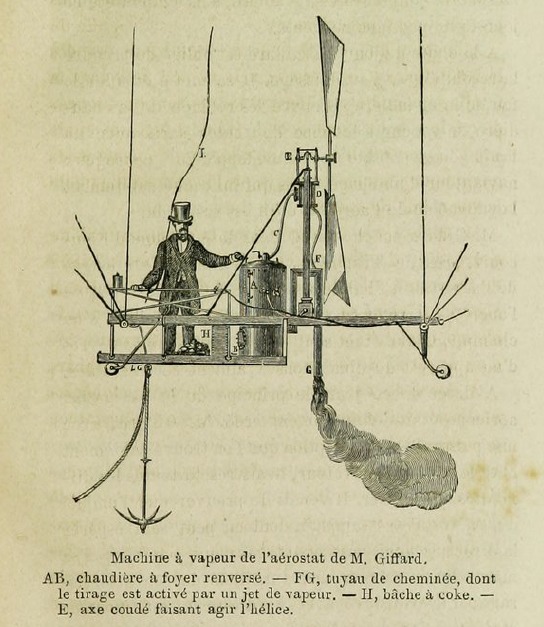

In 1852, Henri Giffard was the first to apply mechanical propulsion to an elongated aerostat. His balloon, equipped with a three-horsepower steam engine, achieved real velocity relative to the air and demonstrated the ability to manoeuvre in a controlled manner under favourable atmospheric conditions.

The twenty-year gap between Giffard’s experiment and Dupuy de Lôme’s 1872 project did not, however, signify stagnation. Giffard continued research into materials, sealing methods, high-pressure engines, and steam condensation systems. This is an important element of the conflict: his project was not a single attempt, but an ongoing process of development.

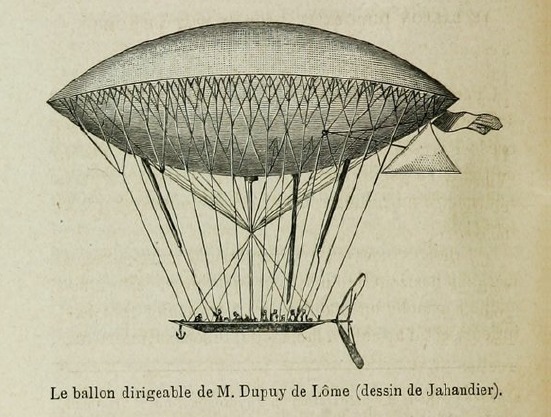

Dupuy de Lôme, operating during the Siege of Paris, received state support and constructed a larger, more structurally stable aerostat, powered by the effort of eight men. Although a similar air-relative speed (approx. 2.8 m/s) was achieved, there was no increase in propulsion power. It is precisely at this point that the core dispute begins.

2. Stability versus Power

The key difference between the two constructions concerned the philosophy of solving the problem of steerability.

Giffard relied on mechanical energy. His project was based on the conviction that the future of aviation depended on engine power, the ability to generate sufficient thrust to overcome the wind.

Dupuy de Lôme focused on stability. He introduced an internal air ballonet, which improved the maintenance of the envelope’s shape and structural balance. It was a practical solution that reduced the risk of deformation during altitude changes.

However, in the assessments of Tissandier and contemporary commentators (Meunier, Figuier, and Moigno), improving stability without a parallel increase in power did not resolve the fundamental problem of controlling the wind. Without sufficient self-propulsion, the aerostat remained dependent on atmospheric conditions.

3. Safety versus Ambition

The decision to abandon the steam engine in the 1872 project was pragmatic. Hydrogen is highly flammable, and the presence of a furnace in the gondola posed a real danger.

Giffard accepted this risk in 1852, designing a steam condensation system and isolating the source of fire. It was an act of technological courage, but also of faith in the future of industrial propulsion.

Dupuy de Lôme chose a safer but less ambitious solution. In this sense, the conflict can be interpreted as a tension between radical innovation and conservative innovation.

4. Political Context and the Memory of Invention

The political context is also significant. Dupuy de Lôme’s project was conceived during the war and financed by the Government of National Defence. It received institutional and public attention that Giffard lacked in 1852.

Tissandier suggests that Giffard’s name was marginalised in official reports. State support shapes historical memory, and institutional narratives carry greater weight than individual experimentation.

Thus, the conflict also exemplifies a mechanism in which recognition depends on political context rather than solely on chronology or conceptual boldness.

5. Technology Ahead of Its Time

From today’s perspective, it is clear that both constructions were limited by the material possibilities of the 19th century. Engines were heavy, hydrogen was dangerous, and fabrics were prone to leakage. The problem was not a lack of ideas but the immaturity of the technology.

Giffard anticipated his era by combining an elongated aerostat with mechanical propulsion. Dupuy de Lôme demonstrated structural stabilisation. Only in subsequent decades, with the development of internal combustion engines and lighter materials, did the great airships of the late 19th and early 20th centuries become feasible.

6. The Significance of the Dispute for the Present

The dispute between Giffard and Dupuy de Lôme is not merely an episode in the history of aeronautics. It is an example of tension between vision and compromise, between energy and stability, between individual experimentation and institutional projects.

In the 21st century, amid the climate crisis and the search for alternative modes of transport, the idea of large, energy-efficient airships is re-emerging. Today’s projects employ technologies that the 19th century could only have imagined.

In this sense, the conflict of 150 years ago remains unresolved. It has been suspended in time.

Perhaps the question of who was right is no longer the most important one. More important is whether the vision that once seemed too bold can now finally be realised in full.

Author/Editor Maria Anna Furman

Source: Gaston Tissandier (1843–1899), Les ballons dirigeables : expériences de M. Henri Giffard en 1852 et en 1855 et de M. Dupuy de Lôme en 1872, Paris: Édouard Blot et Fils Aîné, 1872.